Guest blog by Robin Meakin

Head of Insights

CSM Sport & Entertainment

With interest and investment in women’s football increasing rapidly, a dilemma looms: how to leverage commercial opportunities whilst continuing to service the growing number of fans who crave a less commercialised version of the sport?

It was in June 2020 that Australia and New Zealand were announced as joint hosts for the FIFA Women’s World Cup 2023. A ray of light in the midst of a pandemic which had caused the cancellation of the majority of women’s elite football right across Europe.

The Premier League, La Liga, Serie A and the Bundesliga faced no such curtailment, in what was a depressing barometer of where the game’s priorities lay.

In the intervening years, though, women’s football has exploded, while the men’s game has been beset by controversy. On the one side, record crowds, growing investment and a position as one of the sponsorship industry’s key growth drivers, according to ESA’s 2023 Sponsorship Trends research. On the other, failed Super Leagues and a growing resentment at a sport seemingly out of touch with the community it serves. Fans priced in and fans priced out.

That sparked a few questions. Who are these fans flocking to watch women’s football, why are they watching it, do they differ from followers of the men’s game and what challenges does that pose for the future growth of the sport?

Our annual CSM Fan survey, combined with our proprietary ethnographic research, enabled us to go in search of the answers, digging deeper into the profile of women’s football fans as women’s football showpiece event got under way. Here is what we found out.

—

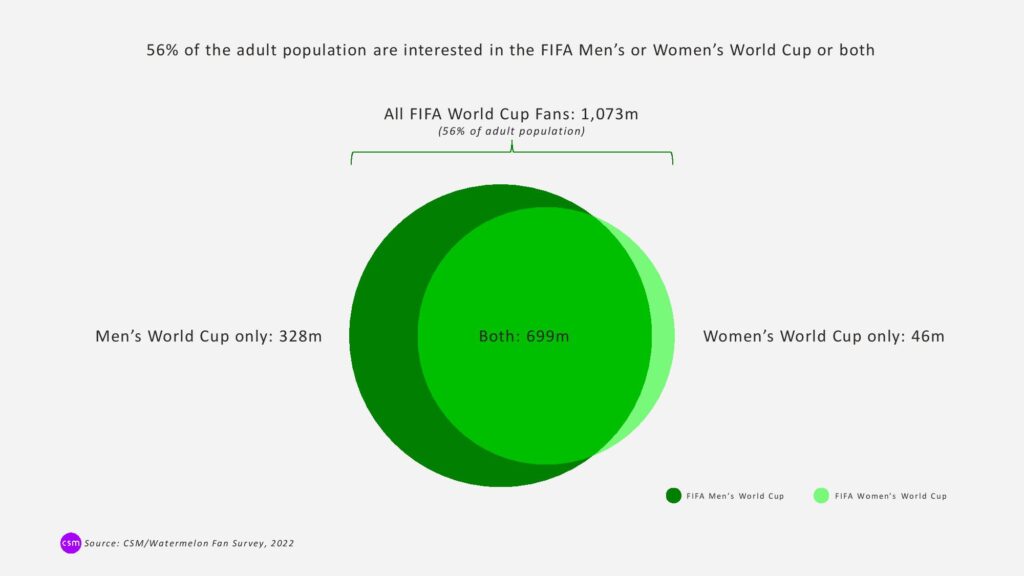

According to data from the survey*, more than one billion people across 30 countries surveyed have some interest in the FIFA Men’s World Cup, while the figure for the FIFA Women’s World Cup is 744 million, equating to 53% and 39% of the adult population (16+ years) respectively.

Within that, 75% of the one billion people following the Men’s World Cup regard themselves as avid fans of the tournament, compared with just over 50% of those who follow the women’s equivalent. There is a clear discrepancy there, but a predictable one given the well-established nature of the Men’s World Cup.

As the women’s game continues its rapid evolution and delivers skilful, exciting football, there’s no reason to think that the current casual fans won’t convert to being avid fans in the coming months and years.

The data also revealed a significant overlap of these groups, with most fans of the Women’s World Cup following the men’s event and only 7% saying they are not interested. That is not fully reciprocated by fans of the men’s competition, 68% of whom are interested in the Women’s World Cup.

The question arising from this is: how do these audiences differ, if at all? In terms of core demographics and economic status, there are indeed some interesting variations.

If we look first at that core group of 699 million people who are fans of both World Cups, the demographic breakdown in gender, age and economic activity is mostly in line with the general population, which is not surprising given its size.

Looking at the 328 million who are fans of the Men’s World Cup only, they skew more towards men (68%), but are also in line with the general population in terms of age and economic activity. The avid fans within this group skew even more towards men (73%), a stat which may not be that surprising.

Finally, the smaller group of 46 million who are fans of the Women’s World Cup only is broadly in line with the general population in terms of gender, but skews a lot younger, with 56% aged under 35.

Looking at the avid fans within this group, this age skew is even more extreme with 64% being under 35. The avid group also skews slightly more towards women at 55%.

So what does all this mean? We can deduce two major observations from this data.

First, there’s a common assumption that the audience for women’s football is primarily made up of women. Our data shows that this is not true.

Yes, women’s football is more gender-balanced than men’s and, as we have seen, avid fans of the Women’s World Cup do skew more towards women than men. But it would be a mistake to persist with the idea that men’s football is for men and women’s football is for women. Men and women like football, especially at international level, regardless of the gender of the players.

The data suggests that age is just as important as gender in understanding fans, and perhaps more so. The Women’s World Cup audience skews young, raising the question: what is drawing them towards the women’s game instead of the men?

Data from our ethnographic research programme, the ‘Weekend Project’, provides some clues. Having talked to younger football fans in the UK, US and Australia, they show a craving for a version of the sport that is less commercialised, more inclusive and more civilised. Right now, women’s football is helping to satisfy this hunger.

At present, their perception and experience of women’s football is that it is more accessible, less commercially driven and, as a result, something they can relate to and feel involved in more easily than the men’s game.

That presents a dilemma. The absence of rampant capitalism is a breath of fresh air drawing fans towards women’s football, yet the game requires and relies on commercial investment to continue developing its own independent value.

How do you square that circle? It seems clear that care will be needed to ensure fans are not alienated as the women’s game grows in popularity and as more money inevitably flows into the sport. I think the key to this is putting a lot of effort into understanding who these fans are, what specifically is drawing them towards the women’s game, what kind of experience they are looking for and the type of partners they will tolerate.

The second observation is that, given the huge overlap between fans of both the Women’s and the Men’s World Cup, the Women’s World Cup is currently a more cost-effective and less cluttered route for brands to reach the same audience that is so coveted by sponsors of the Men’s World Cup.

There is, therefore, a balance to be struck between making the most of the commercial opportunities of the women’s game and avoiding the risk of alienating fan groups through unfettered growth.

It will be a conundrum that women’s football stakeholders will have to consider in the coming years, and something that we can all ponder while enjoying the World Cup that kicked off today.

* The data in this article is taken from CSM’s annual sports fan survey done in collaboration with Watermelon Research. The 2022 version of the survey talked to 34,000 adults across 30 countries. The Weekend Project is CSM’s proprietary ethnographic research tool. To find out more, please get in touch with CSM’s Women’s Sport Lead, Victoria Monk (Victoria.monk@csm.com).